In my most recent prior post, in which I nebulously reflect on what it means to see The Rolling Stones in concert, I mention that their longevity as a functioning band has seemed to actually hurt their image in the eyes of young modern music fans. Since their sound and image has been so incorporated into the broader definition of rock, it’s difficult to appreciate their contributions without prior context.

Mick Jagger is obsessed with being as popular as possible. He constantly pays close attention to contemporary sounds and styles, and consciously works to incorporate these trappings into the band’s music. That’s why they got into disco in the late ‘70s, and flirted with hip-hop inspired beats in the ‘90s. It’s why every single and expanded box set comes chock full of remix after remix, often from many of the most prominent electronic producers of the time. Sometimes it works, but just as often makes the band come off as out-of-touch geezers attempting to chase fads. In any case, while Keith Richards’ dedicated traditionalism always keeps one foot rooted in rock and the blues, there seems to be a concerted effort to not look back. This tendency obscures the through-line of their career.

All this is to say that after 50 years and several iterations, the band is more of a brand now, an all-encompassing cultural touchstone. You’re much more likely to see college students sporting the tongue and lips logo on a T-shirt than you are to hear them actually listen to Emotional Rescue. Nothing is wrong with that per se; it makes sense that new generations want to listen to music of their moment, and not that of half a century earlier. Yet if the band is at all concerned about their legacy moving forward, they should invest more in reminding everyone about what made them so good to begin with.

How to do that? Well, it’s a tough question. Over the past few years they’ve released remastered versions of their classic albums, usually in super-deluxe versions complete with studio outtakes and live sets. However I get the sense that the only people interested in these are those who are already fans anyway, those people who have their vintage edition of Exile On Main St. spinning on the turntable. Besides, all of the re-released albums come from the 1970s, leaving out the entire first decade of the band’s story. Few will argue that the early Seventies was peak Stones, but the Sixties were foundational and more influential in regards to their place in the pantheon. If the band wants to begin to rehabilitate their image, they should start there, at the beginning.

There is good reason to do so. In the Sixties, the music industry had not yet settled on the long player record as the primary means of music consumption. In fact, it was through the artistic advances of artists of the mid-to-late Sixties who affected this change, namely Bob Dylan, The Beatles, and The Who. Prior to them, an LP was seen as only a collection of songs by an artist, only of interest if you were super into them and wanted to buy more than a single. Most people during the decade bought singles – 7” records that had one song on each side. Extended plays, so called because they were longer than singles, contained 2 or 3 songs per side. It wasn’t until Dylan and the like began to use the LP as a medium to express more complex artistic statements that the concept of the “album” took form. Imagine – The Who could not execute Tommy in a medium defined by singles or EPs.

What this means for a modern music fan and record collector is that there are many songs by Sixties artists – often the most famous songs – that were only released as singles and not included in a corresponding album from the time period. Same goes for EP only tracks. This makes it hard for people nowadays to track down everything they want: “Which Stones album is ‘Satisfaction’ on?” Well, it isn’t on an album, unless you buy a compilation. Greatest Hits packages are great, but because they pull songs from different time periods they fail to accomplish what is one of the strengths of a long playing album: presenting a snapshot of the artist as they are at a given time.

Confusion is compounded by the common practice at the time of record companies changing the tracklist of albums depending on where it was released. For example, the American release of Aftermath was different from the British version bearing the same title. Label execs thought they had to tailor each release for the “intended audience,” as if music fans are not going to like a certain song because they live on the other side of the pond! Usually, hit British singles were included on American records at the expense of deeper, non-single cuts. All of this adds up to a confusing and difficult task of getting all of an artists’ material in a concise and convenient place.

The Beatles rectified this in the late 1980s by releasing only the British versions of their albums on CD, and creating the two-volumed Past Masters to collect the spare single and EP-only songs. This became the canon Beatles discography from there on out, and has made it extremely easy to collect their material.

The Rolling Stones, on the other hand, have not done this. You usually find the American versions of each album floating around out there, which leave off more obscure cuts that are next to impossible to hunt down. Even worse, these stray tracks and obscure B-sides can often only be found on expensive and hard to track down box sets. I can’t believe that in 2021 the “world’s greatest rock n’ roll band” has still not consolidated all of their breakthrough Sixties material in a way that makes it easy for fans to hear all of it as intended. If they did so, I believe that the strength of the material will be emphasized and we can begin to rectify their legacy in relation to their more canonized peers.

Part of the problem is probably because the Stones are still an active, living unit, so their primary concern is looking forward. The Beatles have been inactive for 50 years, essentially making any Beatles related project an anthropological one. It’s easy to codify a static subject from the past and frame it in whichever way the stewards of their legacy settle upon. It’s much harder to put a career into context that is still in the process of creating itself. Alternatively, we have to keep in mind that individual song licensing could be a factor, especially with different labels involved through the years in multiple countries.

That said, I’ve taken it upon myself to reassemble The Rolling Stones’ ‘60s material into definitive versions of their studio releases. This means that I have integrated British-only tracks into contemporaneous American studio albums to create an idealized version of the project as a whole. In this regard I’ve taken pains to reflect the original running order of each release while putting the extra songs into the running order in a way that makes sense and sounds good both sonically and thematically.

A side effect of this effort is the remainder of stray tracks that don’t appropriately fit onto albums proper. I’ve divided them into two compilations: one for the earlier ‘60s, and one for the latter part of the decade. For these I used the names of the two most popular existing Sixties era compilations. There’s also one EP length compilation, which I’ll touch on.

So, for your edification as well as mine, I present to you the “perfect” versions of the Rolling Stones’ original releases. For each playlist, I’ve given the year that the original album was released.

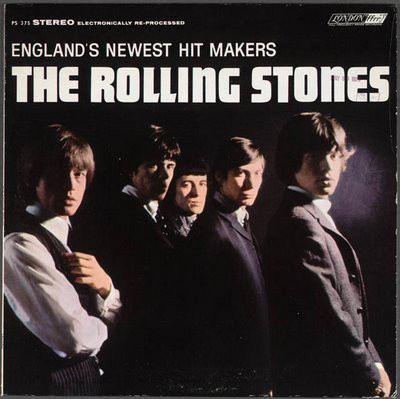

England’s Newest Hitmakers (1964)

The first album, eponymous in the UK but titled England’s Newest Hitmakers in the US (I went with that title – it’s a little more fun) was the easiest to assemble. I just included their fantastic cover of Bo Didley’s “Mona,” (here subtitled “I Need You Baby)” and first original Jagger/Richards composition, “Tell Me.” What’s so striking about this one is how dirty everything sounds. Especially on “Mona” and Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” the band rides the rhythms in a way that sounds way harder than what The Beatles were doing in 1964.

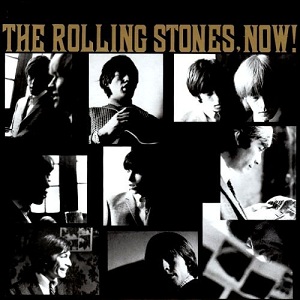

Now! (No. 2) [1965]

One thing that the Stones were much more comfortable doing than The Beatles was jamming. Not that they were a jam band, but they knew the value of stretching out over a good groove. Case in point is the opening “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love,” their version of the classic Solomon Burke standard. The original American release edited almost 2 minutes off of the run time, robbing the track of its libidinous momentum and the album of an explosive opener. As it stands, Now! offers a couple more originals and draws on a slightly broader range of sound. This one, more than any of the early records, highlights the Stones’ influence on garage rock: gritty production, shouted vocals, basis in R&B and the blues, and an energy that overrides any technical limitations.

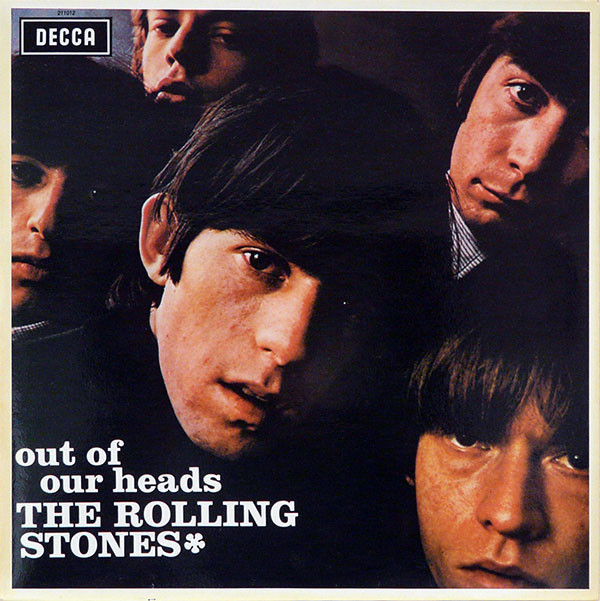

Out of Our Heads (1965)

Out of Our Heads stands as the best encapsulation of the original Stones sound, as by this point they had honed their songwriting craft to produce truly memorable songs that complimented the covers they still performed with aplomb. Exhibit A is “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” the band’s all-time most famous song and one of the history book examples of “Sixties Rock.” It may sound tame by today’s standards, but that scuzzy riff still hits the spot and must have been super exciting in 1965. It’s easy to hear why they were marketed as a rougher, more “dangerous” Beatles. While both were doing essentially the same thing, the Stones have a darker edge to their sound more in tune with the American blues singers they drew from. My favorite addition to this reconstituted tracklist is the addition of “I’m Free” as the last track. It’s the perfect upbeat sendoff.

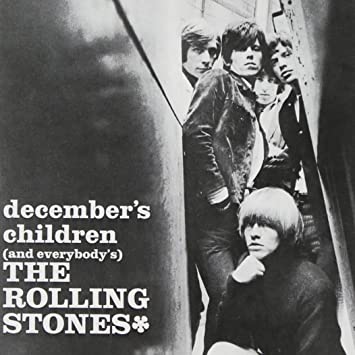

December’s Children (And Everybody’s) [1965]

Next up we have my EP version of December’s Children (And Everybody’s). The Rolling Stones really have a thing for digressive titles. This title comes from an originally US-only release, and I’m using it here for 5 tracks that are a little more advanced than those that make up my first full-length compilation, yet are more traditional than the psychedelic and hard rock trappings that would come later in the decade. Of note is “Get Off of My Cloud,” an early classic and a great example of Charlie Watts’ driving drumming.

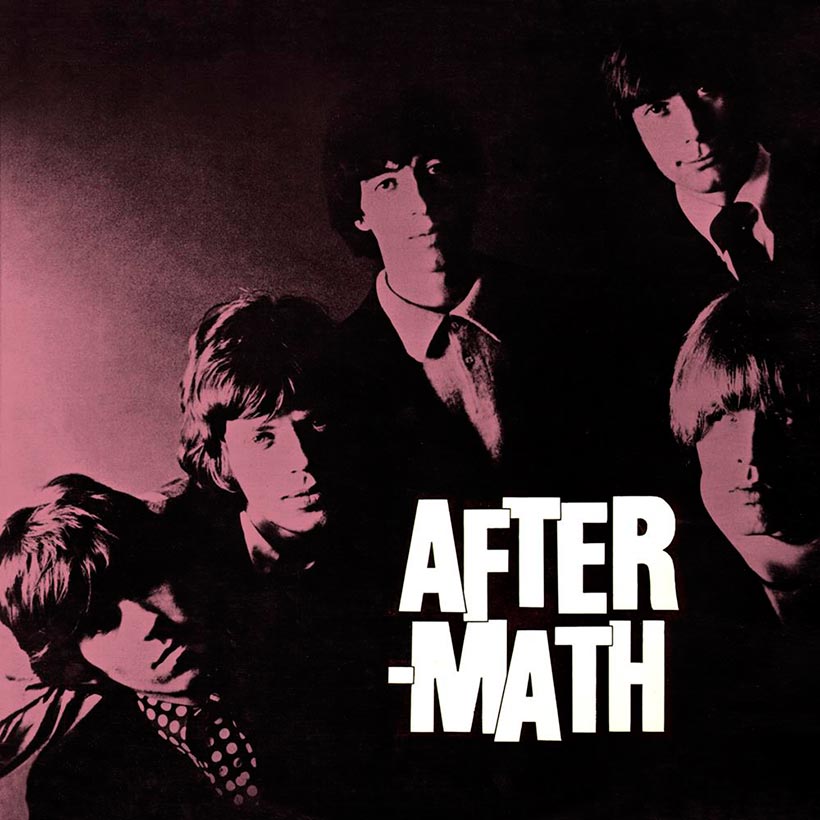

Aftermath (1966)

While Out of Our Heads is a better introduction to Sixties Stones, I think Aftermath is a more interesting listen. The American version (and our’s) opens with the immortal classic “Paint It, Black,” a sign that things are not like what they once were. This is their first all-original tracklist; I used the unedited version of “Out of Time” (put towards the end to help carry momentum through the run time). I want to take this space to point out a couple things: “Going Home” is the longest studio song of the band’s career, another foray into jamming, this time slightly Eastern-tinged. Also, this is as good a place as any to talk about Brian Jones. Jones actually started the band and was seen as their leader and spokesman for much of the Sixties. Nominally their rhythm guitarist, he added tremendously to the music through exquisite slide playing and harmonica (Jagger didn’t start playing until Jones left the band). Furthermore, he was the impetus behind pushing the band away from their blues roots and experimenting more with novel instrumentation. That’s him on the sitar on “Paint It, Black,” and the marimba on “Under My Thumb.” (That marimba riff makes the song, and despite the chauvinistic lyrics, it’s one of my all-time favorites of theirs.) Since Brian Jones died in 1969 and the band continued without him, he is the least memorialized member of the 27 Club. While safe to say that The Stones wouldn’t have created their Seventies masterpieces with him, they also wouldn’t be the band that they were without him, and Aftermath is the ultimate pinnacle of Jones’ positive contributions to the band. Coincidently it’s one the albums, along with The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, that Lennon and McCartney cited as major influences at the time. Not hard to see why.

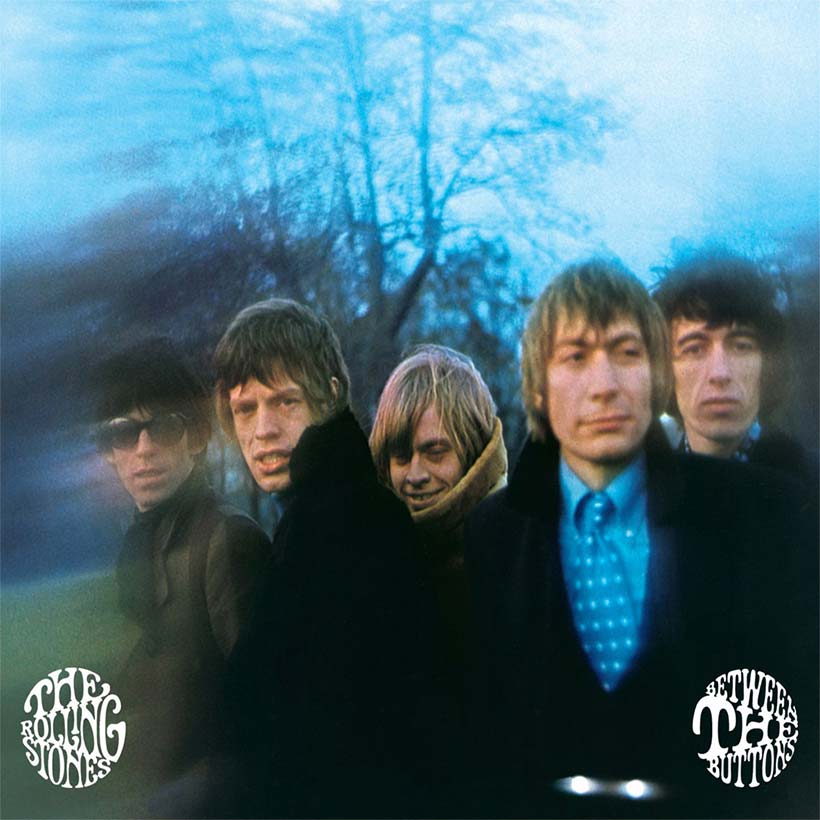

Between the Buttons (1967)

Between the Buttons is probably the most skipped-over Stones album of the decade. It’s often parroted that they did not do psychedelia well, as they were just following trends at the time. This is pretty unfair, as everyone was following that trend at the time, because everyone was living through the counterculture revolution. The Rolling Stone’s version of this sound was more British and fey than The Beatles. Whereas The Beatles were influenced by the American sounds of Dylan and The Byrds at the time, the Stones drew more from a European mindset, and you can tell that they all came from the urbane London scene in how they interpreted that sort of British poshness into their sound. Overall, Between the Buttons is a grower of an album that doesn’t really need the addition of the big singles (“Ruby Tuesday,” “Have You Seen Your Mother Baby, Standing In the Shadow?”) to stand on its own, but they certainly don’t hurt the proceedings. One note: the American compilation Flowers comes up a lot when looking at these mid-Sixties albums. It’s a great listen by itself, but since it doesn’t have a British analogue I found it served best by splitting onto a few different playlists.

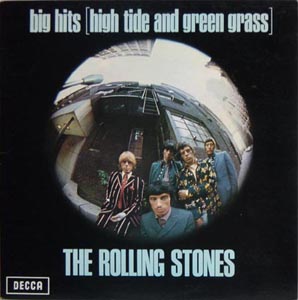

High Tide and Green Grass (1966)

Now we turn our attention to the 2 remaining compilations. The first is High Tides & Green Grass, name taken from the subtitle of the first major Stones comp Big Hits. Included in here are the earliest band recordings, such as their debut EP 5 x 5, as well as B-sides and a few stray singles. Check out their cover of The Beatles “I Wanna Be Your Man,” actually released before the Fab Four’s own version. It’s a great way to directly hear differences in their approach. Overall, the songs on this new High Tides & Green Grass fit the title well, as the simple, bluesy, and fun tunes compliment the down-home vibe that the name suggests.

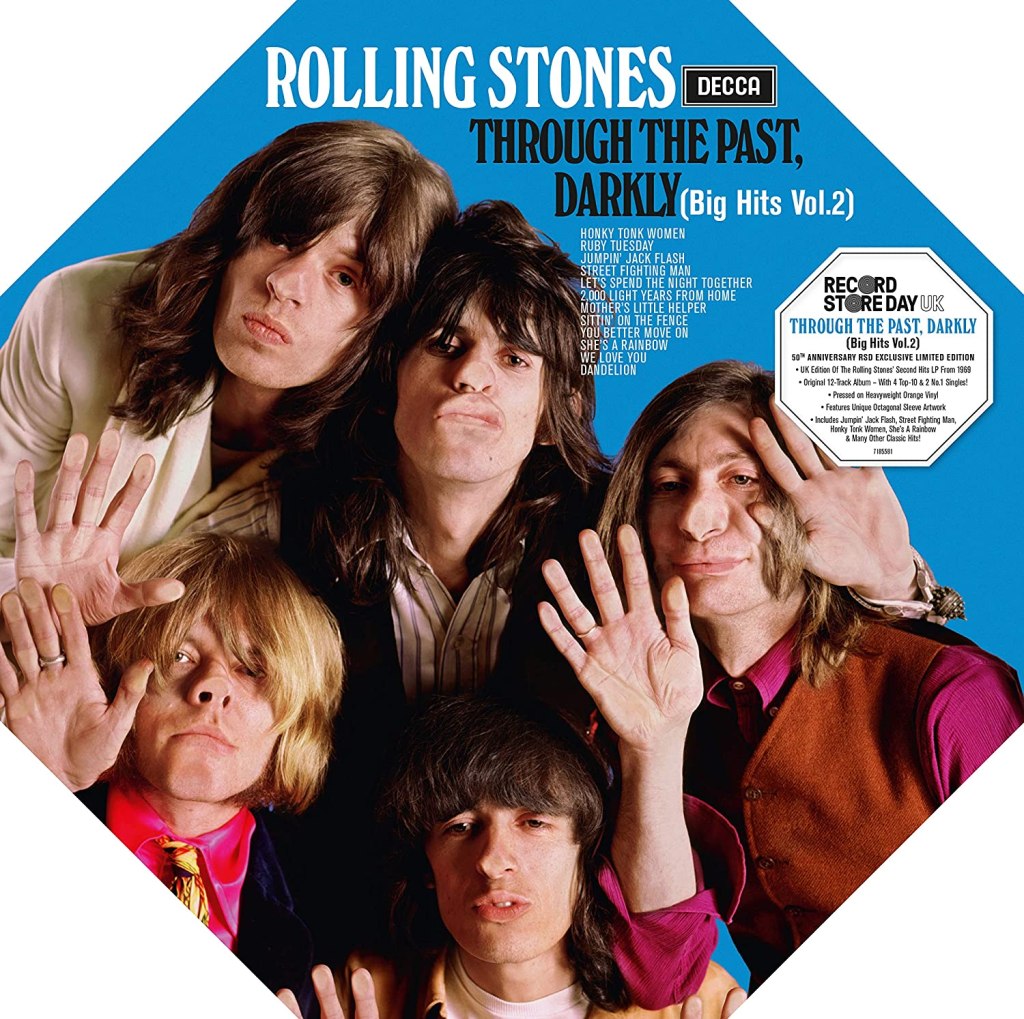

Through the Past, Darkly (1969)

That leaves us with the second comp – Through the Past, Darkly. This was the title given to the second major greatest hits for the band, and it did the same thing I do here: collect the latter half of their career up until that point. However it originally had songs that appear elsewhere in our reconstituted catalogue, so I’ve trimmed those off and added in a few hard to find tracks that fit the overall narrative. The result is a surprisingly tight and listenable 31 minute album in its own right, sporting a very psychedelic theme overall. Of note is “Honkey Tonk Women”, which looks tips its hat to the more hard-edged sound the band would quickly pivot towards. We end our journey through the past with the cool nugget “Natural Magic,” featuring Ry Cooder on some smokey astral slide guitar.

Of course, the Rolling Stones put out three more albums in the 1960s: Their Satanic Majesties’ Request (1967), Beggar’s Banquet (1968), and Let It Bleed (1969). However, they were all released with a uniform tracklist around the world, marking an end for our need to excavate the back catalogue. Also, Let It Bleed was made after Jones had already been kicked out and Mick Taylor brought in to add a more defined lead guitar sound. Keith switched to playing his own now-trademark rhythm, and this new beginning is the true break from what people usually consider “original Stones.”

So there you have it – a tight 5 LPs, 1 EP, and 2 compilations. It took me a few hours to do this, so I’m not sure why no one associated with the band or their record company hasn’t gotten a mind to do the same. Maybe modern internet technology negates the need for an official release of this nature, as anyone can assemble a playlist of songs however they want. Yet my main point remains: The Rolling Stones’ original run of music in the Sixties was just as popular and influential as The Beatles at the time, and stands up today as some of the purest rock n’ roll ever recorded. If more people had access to a coherent presentation of this legacy, I think that new listeners would tap into it, just as prior generations have done, piecemeal, for decades.

<!– /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Helvetica; panose-1:2 11 5 4 2 2 2 2 2 4;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {margin:0in; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif;} h2 {mso-style-priority:9; mso-style-link:"Heading 2 Char"; mso-margin-top-alt:auto; margin-right:0in; mso-margin-bottom-alt:auto; margin-left:0in; font-size:18.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; font-weight:bold;} a:link, span.MsoHyperlink {mso-style-priority:99; color:blue; text-decoration:underline;} span.Heading2Char {mso-style-name:"Heading 2 Char"; mso-style-priority:9; mso-style-link:"Heading 2"; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; font-weight:bold;} span.screen-reader-text {mso-style-name:screen-reader-text;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

LikeLiked by 1 person