AUTHOR’S NOTE and WARNING: This is an extremely long read. Really, I could have written an entire essay on each album (and in some cases did). But I wanted to give each piece its due and situate it properly into context. Not that I underestimate your commitment nor reading comprehension; of course I would love for you to read and enjoy it. However I personally feel that it grew past its original scope and owe it to you to let you know that this isn’t a quick toilet read (unless you really have to go). I wrote this over a period of some time, and several threads emerged that weave in and out of the whole: how Syd Barrett’s breakdown influenced everything about the band subsequently; how Pink Floyd’s music, lyrical themes, and imagery come together to make a whole greater than the sum of its parts; how The Dark Side of the Moon is the ultimate encapsulation of all of this. Shine On.

What is the sound of space? How do we aurally capture the vast star-speckled expanse of the void, the intractable unknown? Just as the universe holds near infinite possibilities, there are countless ways to signify the feel of outer space: clear, high guitar; textured, effect laden electronics; pulsing, spacey rhythms; a beating undercurrent of menace, yet at the same time a touch of austere beauty. Not coincidentally, these same sonic touchstones also describe the music of that singularly monolithic institution: Pink Floyd.

Truly, the Floyd have one of the most recognizable and stereotypical sounds in rock. Ask anyone with even a passing knowledge of music what the band sounds like and they’ll describe echoey soundscapes and elastic jamming. The sound exists in the Venn diagram intersection of blues, psychedelia, and prog, and while countless acts have drawn from them in decades since, none have fully captured the same far-out majesty.

At the same time, there is more to Pink Floyd than atmospherics. Through unified concept albums, the band explored serious themes that range from mental illness, to politics, war, and identity. Yes, there’s even some science-fiction and fantasy thrown in there for good measure. Beyond trite allusions to these subjects, they present genuinely intelligent and poetic ruminations that amount to full commentary. When paired with iconic visual artwork by artist Storm Thorgerson, the band’s releases amount to fully unified works of art. The ideas explored in their songs coupled with the emotions conjured by their sound is profound; Pink Floyd is one of the few bands whose ENTIRE output actually deserves to be delved into and explored.

Of course, there are going to be ups and downs in a career that spans decades, even one as illustrious as Pink Floyd’s. Even though all fifteen studio albums they released between 1967 and 2014 are worthwhile, some are better than others. Yet each retains a singular personality. For novices, I recommend starting with the top spot on this list and moving forward chronologically, then go back to hear their earlier stuff. I say this because it provides an accessible context through which to appreciate their range of sound, instead of jumping right into the deep end. That said, this isn’t a listener’s guide, but a ranking – of all their albums, from “worst” to undeniably best. There’s great stuff to be found in their younger avant-garde years as well as their older more stately material. So set the controls for the heart of the sun, and get lost in the aural world of Pink Floyd.

Lineup:

Bass/Vocals/Guitar/Keyboard (1965-1985): Roger Waters

Keyboard/Synth/Vocals (1965-1980, 1994-2008): Richard Wright

Drums/Percussion/Sampling/Vocals (1965-2014, 2022): Nick Mason

Guitar/Vocals (1965-1968): Syd Barrett

Guitar/Vocals/Bass (1968-2014, 2022): David Gilmour

[As always, this list considers only officially released studio albums. Pink Floyd has released many live albums from every era of their career, as well as several high quality compilations of standalone singles and otherwise unreleased full songs. If you are a fan I strongly recommend a streaming deep dive.]

15. The Endless River [2014]

The almost entirely instrumental The Endless River was assembled and released after the death of Richard Wright. It explicitly serves as a loving farewell to him as well as an epilogue to the band’s career as a whole. As such, the music touches on a bit of everything that they’ve done, yet carries a reverential quality that is unique to this album. At the same time, they don’t bring anything new to the table either, and overall The Endless River sounds most directly like their previous release The Division Bell. Part of this is because a good chunk of material was recorded or partly recorded by the band during the sessions for that album, with finishing touches added after the fact by David Gilmour and Nick Mason. There is one vocal track on the record, closing song “Louder Than Words.” In it, Gilmour waxes nostalgic about the music they’ve made together through the years, affirming that their art is ultimately more powerful and bonding than any past squabbles (looking at you, Roger). It’s a nice sentiment, but ultimately “Louder Than Words” isn’t the strongest song in their catalog, and the rest of the album, while containing some cool soundscapes, blurs together and fails to leave a real lasting impression, especially compared to every other record on this list. The Endless River is a fitting farewell from masters of the craft, but all things being equal it comes out as their weakest release.

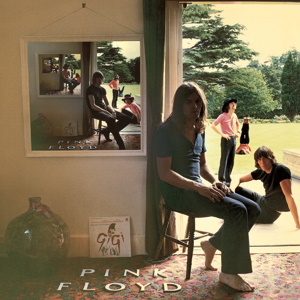

14. Ummagumma [1969]

Ummagumma is an extremely weird and challenging listen. It’s a double release: the first disc is recorded live, the second is in the studio. The live disc is excellent. It showcases powerful extended versions of four earlier songs. Waters’ bass playing is authoritative, and his screams at the climax of “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” are blood curdling. It’s the definitive version of the song, putting the studio take to shame. It’s also interesting to hear Gilmour sing Syd Barrett’s parts, but at the end of the day the focus is on his piercing guitar and Mason’s wild pounding drums. The studio side, on the other hand, is a different picture. The concept is this: each of the four members would write and record their own music, without any help or input from the other bandmates. Like all of their gear disassembled and splayed on the back cover, the band strips itself to its barest individual components. The results are predictably spotty. Wright leads things off with the baroque “Sysyphus,” which utilizes almost every keyboard, piano, and organ sound possible to create a thunderous and classically tinged monolith. Next comes Waters, who turns in the beautifully pastoral “Grantchester Meadows,” one of my favorite acoustic numbers, as well as the absurd “Several Species of Furry Animals Gathered Together in a Cave and Grooving with a Pict.” It’s essentially a collage of his vocalizations warped and treated to make a cacophony of squeaks and squawks, with a little Scottish-accented ranting in the background (hence the Pict). It’s one of the strangest moments in their career of strange moments, but that’s part of the charm of the album. After that, we have Gilmour’s “The Narrow Way,” which starts off as a ballad, turns up into some guitar exploration, then winds back down. Finally, we have Mason’s “The Grand Vizier’s Garden Party,” a percussion experiment augmented by some flute played by his wife. It’s…..interesting, but the inherently amelodic aspect of the track makes it the weakest of the four. This is the sound of a young band trying to experiment, and while it does yield some interesting moments, overall it’s too “out there” to sit next to most of the band’s other efforts.

13. The Division Bell [1994]

For a long time, The Division Bell stood as Pink Floyd’s final album. It works pretty well in that regard, mostly due to defining late-period closer “High Hopes.” It sees the return of Wright behind the keys after he sat out nearly all of the 1980s after being fired by Waters. His return brings back more of the classic Floyd sound. The Division Bell has much more thematic depth than the preceding A Momentary Lapse of Reason, and the production is suitably lush. Lyrically Gilmour focuses on themes of interpersonal conflict – singing about differing perspectives, pride, and reconciliation through time. It’s easy to think that much of it has to do with his departed creative partner Waters, although it’s never made explicit. On the downside, the record could have used a bit of Waters’ creative spark, as many of the songs are stuck in the same slow-to-mid-tempo groove that allows Gilmour to stretch out on guitar, but also lends a sense of sonorous monotony to much of the music. Upon hearing it, one friend of mine described the slinking bass and smooth groove as “porn music,” and now I unfortunately can’t get that comparison out of my mind. There are some good songs on it, and the playing is excellent. Mid-album instrumental “Marooned” stands as the greatest single example of what Gilmour’s guitar “sounds like.” But overall The Division Bell lacks the edge that makes the band’s best work still vital today.

12. More [1969]

More is the first collection released after the exit of founding frontman Syd Barrett. The band is clearly a little rudderless and have yet to congeal around their strengths. There are some good spots here: the opening “Cirrus Minor” sets a great mood, and the thunderous “The Nile Song” is one of their most rocking tracks. Otherwise it’s filled out with some pleasant Gilmour ballads interspersed with a lot of instrumentals. Some, like the rhythmic, twitchy “Main Theme” are more exciting than others (the overlong, aimless “Quicksilver”). It’s honestly not a bad listen if you are in a subdued mood, but as I’ve said about the preceding spots on this list, it doesn’t hold a candle to what would come.

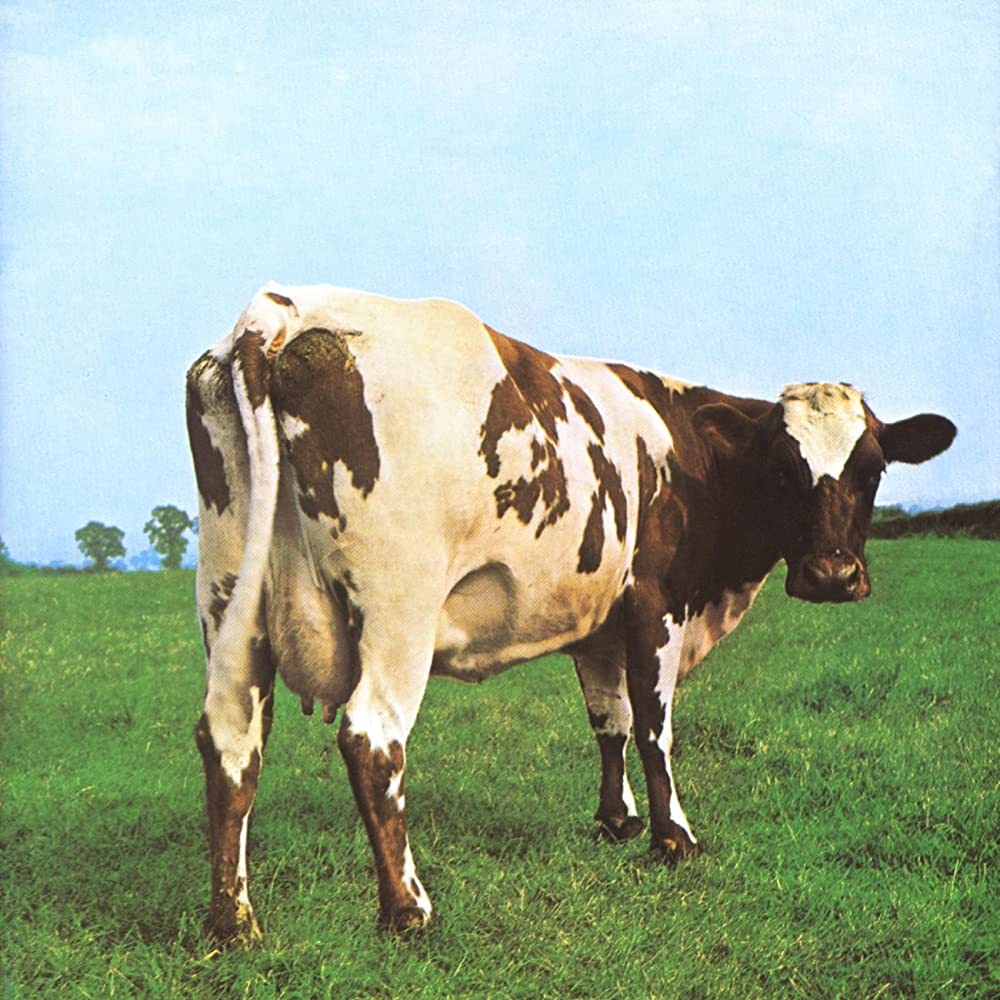

11. Atom Heart Mother [1970]

What a doozy. This is certainly the most bonkers Floyd album, a true love-it-or-hate-it litmus test for fans. First of all, it is one of their most iconic album covers: just a black-and-white dairy cow in a field, staring at the camera. It was chosen by the band completely at random, yet when paired with the music within it takes on a sense of obscure profundity. Now to address the elephant, er, the cow in the room: the title suite, “Atom Heart Mother.” It was written in collaboration with avant-garde composer Ron Geesin, who arranged and conducted a full orchestra and choir live in the studio with the band. Clocking in at almost twenty-four minutes, it’s Pink Floyd’s longest single track. The band described it as a “theme for an imaginary Western,” and it was reportedly considered for the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange before its use was denied. The overall piece is very hard to describe, but it certainly can be said to be impressive; it’s not one you pop on but for when you are kicking back with the good headphones on. The opening odyssey is a big hurdle, but the back half of the record holds hidden charms. Once again the three singer/songwriters get a track apiece, and turn in concise full band songs, contrasting with the rambling experiments of Ummagumma. Roger’s “If” is a tender rumination on insecurity and loving reassurance. Rick’s psych-pop ditty “Summer ‘68” looks back longingly. Dave’s “Fat Old Sun” has a nice drifting melody but is really all about the guitar solo, one of his all-time best. Closer “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast” is an idea from Nick about recording one of their roadies (the eponymous Alan) preparing and eating breakfast, then playing over the tapes to create music that represents and compliments the “breakfast mood.” I’ll let you decide if they were successful.

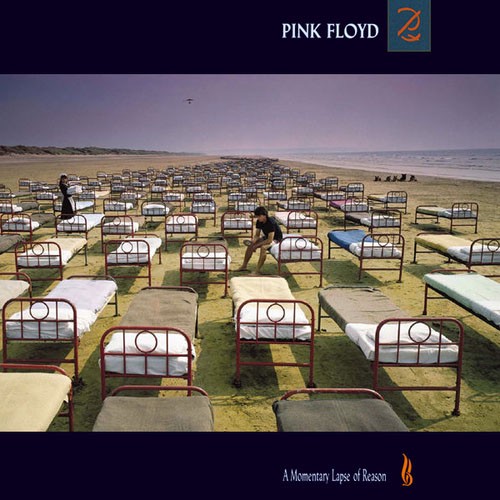

10. A Momentary Lapse of Reason [1987]

A Momentary Lapse of Reason is the first album recorded after the departure of founding member Roger Waters. Waters was a driving force in the group from day one, often spearheading the more conceptual, philosophical aspects of Pink Floyd’s songwriting. In 1985 he quit, claiming publicly that the band “was a spent force creatively,” and struck out to pursue his own path. After a couple years of contentious legal wrangling over use of the band name, Gilmour and Mason reunited to cut A Momentary Lapse of Reason. Besides being one of my favorite Floyd titles, A Momentary Lapse is also an outlier in the band’s catalog for being the only one released as a duo. Without Waters and Wright, the band was drifting for the first time in two decades. It’s also by far their most stereotypically Eighties sounding music with a canned drum sound and overabundance of anonymous keyboard. Despite all this, Gilmour still turns in some very sturdy songs. While not explicit, there seems to be a vague overall lyrical theme of finding human emotion within a mechanized world. “Signs of Life” is a cool introduction, especially for a comeback album, and “Learning to Fly” was a massive hit. “The Dogs of War” is the only song that treads water as it rehashes old moods and topics that had been explored better during the Waters era. Things are redeemed by the compelling “One Slip.” The second side relies on some dated production tricks, but still actually sounds pretty cool, and culminates in the desolate “Sorrow.” Even though it’s often shrugged off by fans, A Momentary Lapse of Reason is pretty good on its own terms, and is one of their more underrated records. Still, the dated production and lack of Waters’ restlessness hold it back from being truly great.

9. Obscured By Clouds [1972]

Obscured By Clouds is the most underrated Pink Floyd album. I never see it get any love. It’s very unfair – this album captures the band at a near peak, developing the same sound and songwriting approach that they would utilize on Dark Side. They don’t achieve full thematic unity, but the vision is there. It opens with the atmospheric title track, then kicks in with a great riff on “When You’re In.” Highlights “Childhood’s End” and “Free Four” respectively ponder coming of age and mortality. Dave and Rick both turn in love songs on the bouncy “Wot’s…Uh the Deal” and solemn “Stay.” And “The Gold’s It’s In The…” rocks! Due to its abundance of instrumentals, I totally agree that Obscured By Clouds is not in the upper-echelon of gold-tier Floyd, but it’s a criminally overlooked gem.

8. A Saucerful of Secrets [1968]

Pink Floyd’s second album is the only one that features all five members together. Due to Syd Barrett’s increasing unreliability (both on the stage and off) the rest of the band brought on longtime friend David Gilmour to fill out guitar duties. Gilmour’s fluid lead lines contrasted well with Barrett’s more erratic rhythm approach to create a sound that was different from yet still tethered to their earlier material. A Saucerful of Secrets is spacier than Piper at the Gates of Dawn, with a bigger focus on instrumental passages than on whimsical lyricism. The disc opens with “Let There Be More Light,” an epic salvo that does a fine job of announcing Gilmour’s entrance. His strong vocals added another layer to what they could do with their arrangements, and the switch between Waters, Gilmour, and Wright vocals to fit the tone of different parts of a song would become a staple for the band. Richard Wright’s presence is stronger here than perhaps on any other record – he takes lead on all but two songs. While he’s not as well known as Waters or Gilmour, the sound of his voice is instantly identifiable as Floydian and he was instrumental throughout their entire career. “Set the Controls For the Heart of the Sun” is one of the essential Pink Floyd songs, a dark trip through the outer reaches of space. However, it and the title track are given even stronger readings on the live side of Ummagumma. There’s also some filler with “See Saw” and “Corporal Clegg,” although the latter is the first glimpse of Water’s burgeoning dissatisfaction with his government’s handling of veterans. I have to finish by addressing the black diamond at the end: closing number “Jugband Blues.” It’s the only Barrett song on the release, and it’s his final songwriting credit for the band. Barrett is well known as one of the greatest flame-outs in rock history, an eccentric genius who literally ate too much acid over time and went insane. “Jugband Blues” is the sound of that insanity, and before going to the dark side of the moon, he sent out this surprisingly aware cry for help. It’s at once a captivating look into madness and a heartbreaking goodbye from one of the true might-have-beens in music. Barrett’s dismissal left a long shadow over the rest of the band’s career. Mental illness and distance between loved ones are core topics that they would explore often throughout the rest of their career, so “Jugband Blues” stands as an inescapable totem on A Saucerful of Secrets. While the whole album is a bit of its time, it is a powerful closing of their first era and the beginning of their transition into something more.

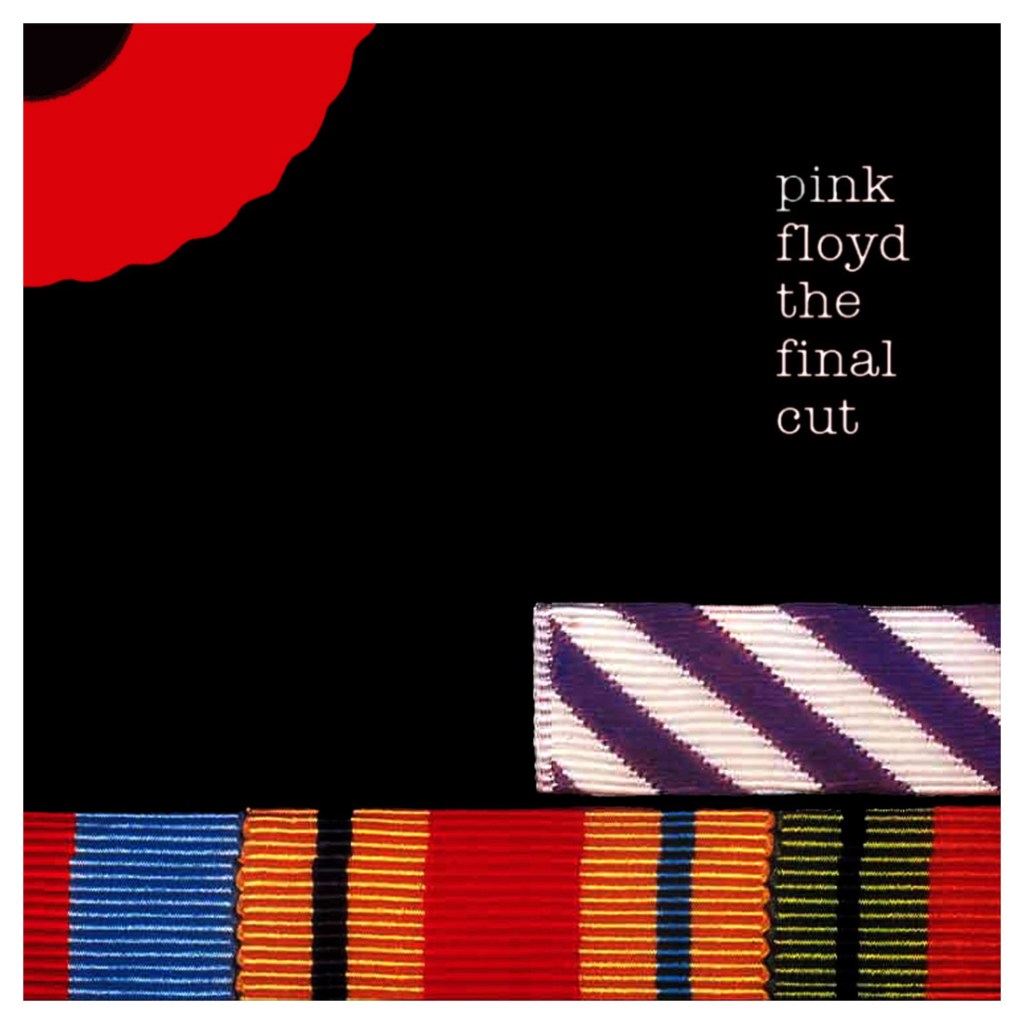

7. The Final Cut [1983]

The Final Cut is officially subtitled “A Requiem For the Post-War Dream By Roger Waters, Performed by Pink Floyd.” It serves as the follow-up to the world-breaking The Wall. After the mega-tour, after the movie, where do you go? The band opted for the intimate with a pseudo-sequel to that 1979 behemoth. Indeed, the subtitle above should clue you in to the state of inter-band relations at the time: Roger composed the entire piece and acts as the musical director. He sings every song save for the late game Gilmour-led throwaway “Not Now John.” The music is spare and subdued, relying mostly on mood-setting tones. There is orchestration, sound effects, and the always present Floydian saxophone. Mason’s percussion is light, and Gilmour’s guitar is used mostly for texture, only erupting occasionally to emphasize moments in the songs – often to great effect. It is obvious that Waters has a clear vision for the statements he wants to produce, and it’s clear why he walked away from the rest of the guys. They were not a spent force musically, but his personal vision and drive sucked all the air out of the room. So The Final Cut is a very singular sonic entity in the Floyd catalog, but it also sounds like no one else. The thing is, it all works within the context of the purpose of the album: to explore the emotional consequences of war. It follows a few different characters whose stories are intertwined throughout the songlist: recovered Pink from The Wall, who looks back on his father’s WWII death in anger; the teacher who tormented him as a lad, now looking back regretfully at his own life; a gunner falling from a plane to his death in the European Theater. Just listen to “When the Tigers Broke Free” and try to not be moved by the end. If Animals is a Roger Waters diatribe and The Wall is his self-crucifixion, The Final Cut is his most deeply thoughtful protest as well as examination of his hang-ups. It all amounts to a striking and emotional experience. Nothing in his solo career, which operates in the same vein and exhibits the same tics, has come close to being this thematically effective and musically rewarding. So while it’s not the best example of Pink Floyd as a band, in another way it’s one of their most successful projects.

6. The Wall [1979]

The Wall. The Wall. Pink Floyd’s The Wall is undoubtedly one of their most inescapably famous projects. It was a massive commercial success when released in 1979, and went on to inspire a motion picture that depicted the story of the album – essentially a music video for the entire tracklist. The film has now become a cult classic in its own right, and inspired some of the band’s most memorable imagery (those fascistic hammers). Due to the ubiquity of the smash single “Another Brick in the Wall, Pt. 2” (which features the “we don’t need no education” refrain) it is where many people’s minds go when they think of Floyd. Because of all this, the actual record’s reputation precedes itself. It’s not my favorite Floyd album by a longshot, but it is one of their most undeniable. The double record tells the story of a man named Pink, who as a child loses his father in World War II, is belittled by authority figures as a school boy, and grows up to become a rock star. Once rich and famous, he ends up alienating those he loves the most and closes himself off from the world (the metaphorical wall). He then loses his grip on reality and begins to see himself as a fascist dictator, directing the adulating masses at his concert to riot. Upon witnessing the destruction, he puts himself on trial and “breaks down” the wall, learning to embrace himself and others through art. It’s clearly patterned after how Roger Waters sees himself, and wants to push the message that society and stardom are cruel to “bleeding hearts and artists.” As rock operas go, it’s one of the most cohesive – once familiar with the story you can clearly follow the plot from song to song. The Wall is Floyd’s most commercial sounding release, with big hooky choruses, late Seventies production, and an almost disco pulse to much of the material. Yet there are also many song fragments and instrumental interludes that connect the scenes of the rock opera, all of varying intrigue. The thing about The Wall is some of the songs only work in the context of the broader narrative, yet others can stand alone among the most powerful in their oeuvre. “Mother” is one of the purest encapsulations of adolescent frustration recorded. “Goodbye Blue Sky” is a beautiful elegy for those lost to the wanton destruction of war. “Young Lust” captures the seedy Seventies nightlife feel perfectly. There’s also “Comfortably Numb.” I’ve talked a lot about the soundscapes and conceptual writing of the band, but I haven’t given enough ink to how great of a guitarist David Gilmour is. He truly is one of the best ever. “Comfortably Numb” is his single greatest showcase. It’s a good song all around, detailing Pink’s reliance on drugs to feel anything in the midst of his psychosis. Yet the track is made by its two guitar solos. The first is a burst of light after an unusually long stretch of darkness in the middle of the album, and is a shining, melodic uplift that reflects the singer’s haunting childhood memories. The second solo, that rides through the outro, is a masterclass in tension and release. The pain and yearning that pours from the six-string is out of this world, a torrent of searing notes that is certainly one of the most powerful guitar solos in rock history. (I want to note how Nick Mason provides subtle support on the drums with well-timed cymbal flourishes). Listen to The Wall for “Comfortably Numb” alone, stay for the rest of the complex sequence. It’s Floyd’s longest release and admittedly I really do have to be in the right mood for it, but like I said, it’s one of the most singular rock records of all time.

5. The Piper at the Gates of Dawn [1967]

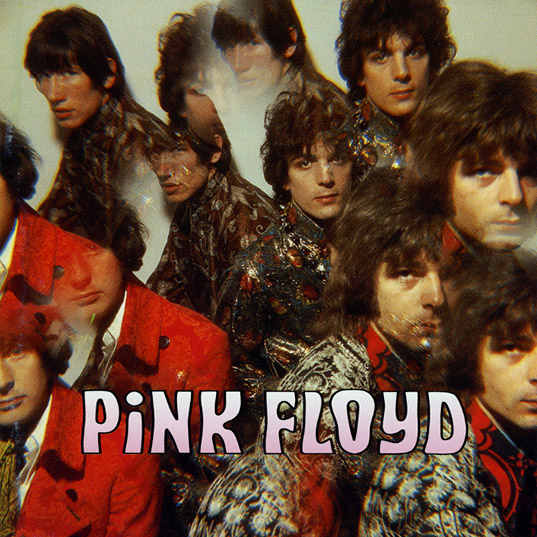

The Pink Floyd that debuted in the mid-Sixties was quite a different beast than the one that ruled arenas a decade later. After playing together under several other names [including The Screaming Abdabs (with guitarist Bob Klose), then Tea Set] friends Syd, Roger, Richard, and Nick took their group name after two blues musicians that they admired, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. The Pink Floyd Sound the band became regular performers at the groovy London venue UFO Club, and before long got signed in 1965 with a cripticly abbreviated name. Over the first several years of their career, Floyd put out a handful of standalone singles (very quality, and included on a bonus disc on some reissues of the album), but their full length introduction was The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. The title came from the novel The Wind in the Willows, apparently a childhood favorite of Syd’s. Piper is one of the greatest artifacts of the psychedelic era. Everything, from the disorienting music, to the Lewis Caroll and Eastern philosophy inspired lyrics, and even the kaleidoscopic cover photo, scream 1967. Yet it’s not cheap or kitschy, because the songs hold together through catchy melodies and adventurous, energetic playing.

“Astronomy Domine” is one of the all-time lead tracks, beaming in from the far reaches of the cosmos to mingle with fairies. It must have been epic live, loud with a light show. Elsewhere the hard rocking “Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk” is the only track written and sung by Waters (his first!). The star of the show is “Interstellar Overdrive,” a 10-minute instrumental that rips from the gun with a grungy riff that transitions into some complex interplay before spacing waaaayyyy out and orbitting around until coalescing back into a phlanging original riff. Fun fact: “Interstellar Overdrive” is the song I heard, as a snippet, on some random Discovery Channel miniseries about the history of rock back in high school that made me think, “hm, is Pink Floyd cool?” because it seemed much rougher and “hard rocking” than my preconceptions. The proceedings end with “Bike,” a whimsical nursery rhyme that in just three minutes descends into madness.

Unfortunately, the same would happen to Syd Barrett after just 3 years in the limelight. It’s suspected that his drug use exacerbated underlying schizophrenia, which led to a mental breakdown. The rest of the band was forced to phase him out and eventually replace him with David Gilmour after about a year of them playing together. Barrett did release two solo studio albums after his ousting – 1970’s dual The Madcap Laughs, which was produced by Waters and Gilmour and backed by the Canterbury-based band Soft Machine; and Barrett, produced by Gilmour and Wright, on which they both back him up. Both are good, and helped establish Barrett as a cult figure fulfilling a demented jester stereotype. However it is The Piper at the Gates of Dawn that is Barrett’s magnum opus; one that does gain mystique from its backstory, but is also the fullest example of his wild artistic vision musically. Barrett’s lyrics, often sung in tandem with Wright, were evocatively imagistic, walking the line between nonsense and profundity like a Cheshire cat poet. While his guitar playing is as not as fluent, tonally rich, or bluesy as Gilmour’s, Barrett’s experimental, effect laden approach is gripping in its own right, and he is backed by a band that has the creativity and talent to go with him. The record’s success enabled Pink Floyd the leeway to explore over the next several years as they figured out the band they would become without him. While Piper at the Gates of Dawn doesn’t fit in with the big Floydian epics to come, it stands as one of the best examples of psychedelic rock in all its disorienting, cracked brilliance.

4. Animals [1977]

Dystopian. The word connotes a sinister authoritarian government oppressing its faceless populace, hoarding freedoms and money by manipulating the truth. It brings to mind the literary classics Brave New World, Fahrenheit 451, and 1984. George Orwell’s 1984, in fact, is the most popular conception of the genre and serves as a major influence on Pink Floyd’s 1977 masterpiece Animals. While it’s probably the least famous of their “Big 4” legendary ‘70s albums [Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals, and The Wall], that’s to everyone’s loss. Animals is their heaviest record, their hardest rocking, and lyrically their most pessimistic. Tonally it’s a bleak experience, but one that is well worth the plunge. There’s also only 5 songs on the entire disc, and two of them are under a minute-and-a-half. So that should give you an idea of the behemoths that we’re dealing with here. Basically, Waters takes Orwell’s Animal Farm and applies it to Thatcher-era Britain. He breaks down society into three types of people: dogs (the blindly loyal enforcers), pigs (the corrupt and greedy rulers), and sheep (the blissfully unaware everyman). The album opens with the acoustic “Pigs On the Wing (Part One),” before leading into “Dogs,” the album’s epic at 18 minutes. The Gilmour led piece is amazing, a look at the entire life of a man who does what he’s told but gets to the end feeling cheated. The guitar is gnarly throughout, and it shifts through many different sections to make a truly monumental slab of prog rock. The 11 minute “Pigs (Three Different Ones)” is about three specific people, but only one – Mary Whitehouse, a British morality campaigner of the time, is called out by name. It’s a nasty and funky exercise with talk-boxes and cowbells, and still comes across as scathing. Finally there is “Sheep.” It is the shortest at only 10 minutes, but contains so much goodness. The riff is galloping, and then the perversion of the Lord’s Prayer in the middle part is darkly funny. Finally the sheep revolt and ride out the day on a rollicking riff. Things settle down on the closing “Pigs On the Wing (Part Two),” where Roger assures us that he cares, and that we’re all in it together. But when do pigs fly?

3. Meddle [1971]

PF fans reading this probably know that there is one song that places this album so high. Yet it’s the last one, so I’ll turn to the rest of the tracklist first. Whereas most Floyd releases have a defining conceptual theme, that of Meddle is more of a defining musical mood: it feels like a misty moor, or the peaceful mouth of a salty cliffside cave that looks out to a stormy sea. It opens with “One Of These Days,” an intimidating instrumental that’s one of the band’s heaviest moments. We then move onto the appropriately billowy “Pillow of Winds” before the bouncy “Fearless,” which is the catchiest number on the album and by the end warps into a soccer chant. “San Tropez” is as laid back as its title, and then the instrumental “Seamus” is nice save for the sound of a dog yowling throughout. The second half of the runtime consists of the elemental “Echoes.” Beginning with a lone piano ping into the void, “Echoes” is a masterclass in sustained mood and sonic exploration. As the song comes together, it transitions through atmospheric haze toward a grinding funk. The mind-bending middle section uses astral sounding whale song, before kicking back in with a Gilmour guitar line that sounds like a ray of sunlight splitting the clouds to shine upon the leviathans of the deep. The track is hard to describe in words without using vagaries; it must be experienced for itself, preferably loud on a rainy day. “Echoes” is the definition of epic and the culmination of the first half of Floyd’s career. It is the moment where their wanderings in the post-Barrett forest of sound solidified into the artistic vision that would define their Seventies output. The fact that it’s paired with a worthwhile set-up in the first half pushes Meddle up to their third best album overall, behind only two unimpeachable, all-time-great classics.

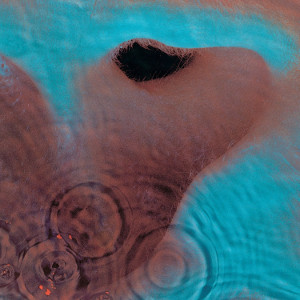

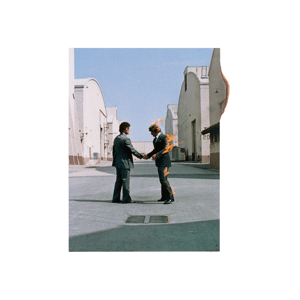

2. Wish You Were Here [1975]

There is a melancholia that infuses Wish You Were Here. From the instant that the needle touches vinyl, and that glass tinkles out of silence, you feel both bright and nostalgic. In many ways this album is the most stereotypical sounding Pink Floyd release, but not in a way that is cliche or corny. It’s the most Floydian because it most embodies the trademarks that set the band apart from their peers. Earlier in this article I talked about how Syd Barrett’s initial leadership and then mental breakdown cast a long shadow over the rest of Pink Floyd’s career. With You Were Here is the apotheosis of that grief, combined with bitterness over a music industry that treats people as commodities. Despite a seemingly dark, depressing thesis, Wish You Were Here is a pretty record, one of the warmest in their discography; this warmth makes the emotions more genuine.

It starts off with “Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts I – V),” at thirteen minute ode to Syd. It is a grand and stately song, with some of Gilmour’s most beautiful guitarwork. Actually it may be tightest that Pink Floyd has ever been as a band, and even Waters gives one of the strongest vocal performances of his career. You can hear the love for his friend and sadness over his fading. From there things shift gears (pun intended) into “Welcome to the Machine,” a proto-industrial track with tons of crazy synth sounds effects. Rick Wright must have had a field day in the recording studio. Side Two begins with the slinky “Have a Cigar,” which is the most straightforward rock song on the record but is also an anomaly. It’s sung by Roy Harper, an idiosyncratic folk singer who never made it big in the mainstream but had tons of admirers in the industry. Waters couldn’t sing it because he hurt his voice recording “Shine On,” and Gilmour refused because he couldn’t get a feel for the lyrics. Yet Harper turns in a perfect performance, sung from the perspective of a cynical record executive. It gives us the fantastic line “Oh by the way, which one’s Pink?” winking at the fact that clueless suits don’t even know the acts that they sign. Next comes the title track, one of their most famous and one of those “forever songs” that everyone knows and loves. It is a bittersweet lament for missing a loved one that feels somehow both forlorn and laidback. “Wish You Were Here” slides into “Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts VI – IX).” It starts out stormier than the first half yet eventually settles back into its familiar motif before resolving into tendrils of horn synth fading away. It makes me think of what the soundtrack to heaven would be like.

Apparently, during early recording sessions for the record, Syd Barrett stopped by the studio. It was the first time that anyone had seen him in several years. He had gained weight and shaved all the hair off his body – including his eyebrows. (The look inspired a memorable scene in The Wall movie). They say that he didn’t even introduce himself for a minute, just came by and started hanging out. They visited quietly for a bit and then sent him home, a little shell shocked. You can feel the conflicting emotions all through the the performances. But really, like with The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, you don’t need to know the backstory to appreciate the resonance of the music. Like much of the totemic iconography of their image, the sound simply IS.

Overall WYWH is an sublime album – haven’t event mentioned the iconic arresting album art – a beautiful tribute to far off friends, and one of the stone-cold-classics of Seventies progressive rock.

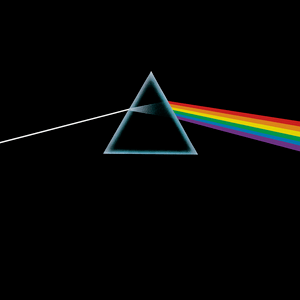

- The Dark Side of the Moon [1973]

A heartbeat. The most primal sound – it’s the first thing we hear as unborn babies, and it undergirds everything we do until our final day, when it stops. It is fitting then that a heartbeat is the first sound you hear on Pink Floyd’s magnum opus The Dark Side of the Moon, as the record is an examination of life’s universality. Each song concerns itself with common stresses: time, obligation, violence, greed and want, mortality, drugs, and mental illness. Throughout are placed snippets of recorded conversation produced by prompting interviewees with questions such as, “Are you afraid to die?” and “Have you ever been in a fight? Were you in the right?” The soundbites are extremely effective, as they enhance the mood of each song and add heart to the spaciness. It all creates a collage of the human experience, and by the end the band sums it up with a remarkably uplifting confirmation of solidarity. In a lesser group’s hands, these themes could dissolve into empty platitudes, but Floyd are able to convey a multitude of perspectives in a way that is convincingly both personal and cosmic.

As detailed in this list, most of PF’s projects have a central concept that all elements of the release play into: the lyrics, music, production, and packaging. Dark Side is their most realized example. Fitting for an album with such esoteric themes, one of the most notable aspects of DSotM is its sonic lushness. Layers of organ, synth, and guitar envelope the listener while heavenly choral backing vocals and languid saxophone throughout imbue the work with import. It’s overall much more user friendly than anything the band had put out prior, yet still carries the sense of adventure and depth that had come to signify Pink Floyd. Mad kudos to producer Alan Parsons for focusing the band’s abstract vision to engineer a perfect record.

The proceedings kick off with the quick “Speak to Me,” a montage of samples from the album to come that aurally depicts birth. Upon being born, we “Breathe.” After “Breathe” we rush into the dizzying instrumental “On the Run,” before crashing down to near silence for my favorite Pink Floyd song, “Time.” The ticking of a clock erupts into a cacophony of alarms and chimes. (Fun fact: those aren’t samples – Parsons actually assembled a room full of clocks and set them to all go off at once!) From there “Time”’s long buildup exemplifies the attention to detail that marks the entire record. Besides sounding great when the drums kick in, the band’s entrance on the track is slightly behind the beat. This jolts the listener and subtly sets them up for a song about…not having enough time. (Get it?!) “Time” climaxes in a soaring Gilmour guitar solo, an amazing display of emotion through a six-string. After a brief reprisal of “Breathe” things wind down for the final song on Side 1, “The Great Gig In the Sky.” This track is famous for the absolutely unbelievable vocals from session singer Clare Torry. It was composed by Richard Wright, who told Torry to simply improvise wordlessly over the music. His only direction was that the song is about death. She knocks it out of the park – her wailing sounds almost inhuman, and is somehow at once both mournful and celebratory. It’s immensely impactful in a way that words could never be; Torry rightfully now has a co-writing credit on the track.

Side 2 begins with “Money,” the big hit single. It’s notable for using the sounds of a cash register to create a beat over which Waters lays down a tricky bassline. It’s a pretty biting song – the lyrics cynically look at the effects of having too much money and, conversely, not enough. It packs in another searing lead from Gilmour. Next up is Richard Wright’s only lead vocal, the moody “Us and Them.” This song, about confrontation and division, comes closest to the hazy Floyd of the prior half decade. It contains echoey vocal effects and a drawn out instrumental interlude that features a luscious sax solo. The third and final instrumental on the disc is “Any Colour You Like,” supposedly about the drug experience but is really a showcase for Gilmour and Wright’s interaction, the former’s wah-wah guitar trading off with the latter’s appropriately multicolored synth runs. Like any gamble with substances that alter perception, you run the risk of insanity, and as Roger Waters reminds us in the subsequent “Brain Damage.” It’s clear that former bandmate Syd Barrett’s breakdown weighs heavily on him, but to a larger degree mental collapse seems to be the only outcome of the constant stressors examined over the previous runtime. But wait! “Brain Damage” abruptly veers into the concluding “Eclipse.” “Eclipse” is a culmination of all that had come before, in which Waters lists off “everything under the sun,” and affirms that in the end, it’s all “eclipsed by the moon.” The monumental climax fades, and we are left with the heartbeat, beating on.

As I write this, I feel like I keep falling back on the same vagaries to describe Dark Side, and Pink Floyd in general: grand, universal, colorful, genuine, resonant, etc.. But that’s kind of how it is with all great works of art. They defy easy description, and must instead be experienced firsthand. I first experienced DSotM when I was 15 years old. I borrowed a CD copy from a friend in my ninth grade class and listened to it that night in bed on an old CD player with headphones. To this day, it is the greatest single listening experience of my life. For 45 minutes I lay lost in the dark as sublime sound ran through my head. The music conjured a rainbow of images in my imagination, and by the conclusion I was genuinely moved. I know that much of the impact came from me not being exposed to that much music at the time. Yet ultimately these relativities are moot; I can sincerely say that hearing it that night changed my life. It made me realize the scope of what could be done with a rock record. More than just a sequence of songs, an album can stand as a unified work of art that conveys meaning. It’s with that mindset that I’ve approached all music since.

I don’t think I’m alone here. Which is, of course, the point of the entire project. Dark Side has resonated deeply with the world at large. It spent 18 and a half years on the chart (a world record), and it still holds a sacred spot in the hearts of music lovers. That’s because, through the piece, Floyd made a sincere statement with which anyone can identify. Despite all of the stresses and hardships of life, we all persevere. Everything in life, the big and the small, the good and the bad, comes together to make this one-of-a-kind experiential adventure that we all share. Through it all, there’s the sense of the deeper, ineffable unknown – the dark side of the moon. Nothing captures the oblique grandeur of this thesis like the prism artwork on the cover. Indeed, is there any more iconic rock-associated art? The black prism fractures white light into its myriad components, just as the broad themes within can mean something different to everyone. That prism serves as a beacon for all creatives who yearn to go deeper.

More than Pink Floyd’s masterpiece, The Dark Side of the Moon is truly the greatest album of all time. There, I said it. As for me, I’m still trying to get back to that feeling conjured by my initial listen all those years ago. I may never get there, but Dark Side has lost none of its impact; listening to it now is still an all-encompassing experience. And like the best art, it inspires me to keep searching.

Conclusion

Syd Barrett retired from public life in 1972 after a couple years of sporadic touring. He lived the rest of his life in quiet modesty in England, mostly painting and gardening. Because the rest of the band gave him residuals for the rest of their career, he never had to work. He died of pancreatic cancer in 2006. The surviving band members are never less than loving in any public comment.

Richard Wright released a handful of lowkey solo albums over the years, and passed away in 2008. This marked the formal end of the band as a functioning unit in any capacity.

Nick Mason produced a couple New Wave bands before getting really into vintage automobiles. He currently tours Britain with his own band called A Saucerful of Secrets, which plays exclusively Sixties era Floyd.

David Gilmour and Roger Waters have spent most of their time apart feuding, to the point that I’m not even sure if they know why they dislike each other. They’ve had occasional detentes interspersed with mudslinging. Both have released a handful of albums that demonstrate their respective strengths and limitations. Waters records are easy to respect but hard to like: conceptually complex and intriguingly atmospheric, they lack the melodicism and musical color necessary to make the ideas truly pop. Gilmour is easy to like but hard to respect: his releases are full of his elegiac guitar soloing and strong voice, but overall feel a little safe and aimless. Both miss Wright’s weight and musicality, just as they miss the tension supplied by Mason’s drumming. Like most of the best creative teams, they need each other. They are the yin and yang of Pink Floyd. The Lennon and McCartney. (Obviously, we know which is which.)

It’s sad to see Waters, especially, descend into petty jealousy and vindictiveness, as well as start publicly speaking in favor of authoritarian states Russia and China. Gilmour and Mason recently reformed as Pink Floyd with a couple of studio musicians, to release a single in support of Ukraine.

I choose to ignore the bickering. Because at the end of the day, it won’t take away from the musical masterpieces that the collective produced. Records like The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here will always be relevant to people because they capture perfectly the struggles with which we grapple. Powerful music, thoughtful lyrics, and unique images – as I’ve said, Pink Floyd’s sound is singular. And these pieces of music will always be here to facilitate trips into both the outer, as well as inner, spaces.