Fire On the Mountain

In July of 2007 my high school cross country team traveled to just outside of Boone, North Carolina for a week long training camp. It was nothing official; in fact, we could not technically refer to it as training, or even a team event, as FHSAA rules prevented practice before a certain date. It was officially just a group of friends who all happened to be on the same cross country team, traveling with a few parents and another man who just happened to be their coach.

We piled into a transport van, schlepped the 10 hours up from Florida, and eventually pulled into a rental cabin nestled in the woods by a stream. We had morning and afternoon practices everyday, which mainly consisted of interval training, pacing exercises, and hill work. In between practices, we spent our time exploring the forest, swinging on a rope swing into a nearby river, and generally goofing around as teenagers on an unofficial trip do. We put in a lot of miles that week, but no workout was as tough as our mountain climb. One morning, we drove a few miles from our cabin to the base of Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. Our coach’s directive: run to the top.

It was a slog. The uphills were brutal, and the occasional descents were treacherous. Yet the mountain’s forested beauty was breathtaking, and it was on that ascent that I first felt a real bond being formed between me and my other teammates, especially one who would go on to be a lifelong friend.

About halfway up we came to the state park from which the rest of the trail continued. Yet we had already been running for hours, and we were exhausted. Our coach mercifully decided that we had already proven ourselves and offered to shuttle us back to the cabin. We gladly took up his offer. As a means of celebrating our efforts, Coach’s soundtrack on the way back was the Grateful Dead song “Fire On the Mountain.” It was extremely apropos: not only had we felt the fire in our legs and lungs as we ran up the mount, but the song also begins with the immortal lines “Long distance runner, what you standin’ there for? / Get up, get out, get out of the door.”

The song is not really about distance running; it’s more of a call to action in regards to personal realization. To our high school ears the music was goofy, with a loping beat that did not lend itself to running. Yet for the rest of the week, whether during warm ups or during a run (in which Coach would drive next to us), we heard that song. It became the theme song for our entire season, and I still have my ‘07 Chamberlain High School XC shirt with FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN emblazoned across the back. I knew that the song would become a nostalgic memory for me through the trip and our collective experience as a team, but at the time I was unaware of the significance that the band who performed it would come to have in my life.

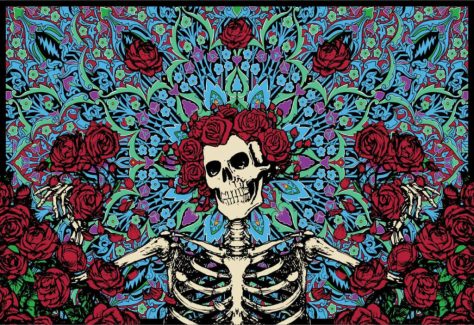

The Grateful Dead are one of the most infamous bands in American rock history. Originally springing from the San Francisco underground in the Sixties, they wound up pioneering the jam band scene and laying the blueprint for continued success outside of the mainstream music industry. Over the decades they became the tie-dyed standard bearers of the remaining counterculture. Even though they have been effectively disbanded since 1995 (outside of brief reunions), their fan base continues to thrive generation after generation. In fact, just as famous as the band itself are its fans: Deadheads. Deadheads are notorious for their devotion to their favorite band, often following them on tour from show to show. Concerts became traveling carnivals with a thriving micro-economy. Outside of touring, Heads trade tapes of live shows, and have developed a language shorthand that can come off as inscrutable to the uninitiated.

Am I a Deadhead? I guess by strict definition, I am. I love the band, I have my favorite eras and lineups, and I even own more than one tie-dye shirt. At the same time I feel like there’s often a stereotype attached to admitting Dead fandom: that of a burnt-out hippie. Yet there is so much more to the band and culture around them, encompassing everything from philosophy, to history, art, fellowship, and discovery, all in a way that is tethered to a distinctly American experience. I owe it to my blog to delve a little into what makes the Dead so great(ful), what they mean to me, and why I think they offer a little something for anyone who possesses an adventurous mind.

Playing In the Band

The Grateful Dead were founded in 1965 in Palo Alto, California. Originally called The Warlocks, the five founding members had been floating around the San Francisco music scene for a while. Lead guitarist Jerry Garcia was a respected folkie who had mastered the banjo. Rhythm guitarist Bob Weir was a fun-loving student with an interest in rock’n’roll. Bassist Phil Lesh was a graduate student of classical music, a trained trumpeter with an interest in experimental composition. Drummer Bill Kreutzman, schooled in R&B and jazz, was known for playing with many formations of musicians in the area. Organ/harmonica man Ron “Pigpen” McKernan was a blues aficionado whose father was a radio DJ.

When the five young men finally came together as The Warlocks, they gigged at bars, restaurants, and parties like any other local group. After a year they changed their name because they heard about another band called The Warlocks. (Interestingly, that other group was another seminal Sixties outfit from New York City who would go on to change their name as well – to The Velvet Underground.) For a new name, they settled on the Grateful Dead, a term that comes from medieval European folklore. Supposedly, if you arranged a respectful burial for the departed, their spirits would grant you a boon as thanks. It turned out to be the perfect name, as it encapsulates the otherworldly mystique that informs so much of their experience. Also, it provided for lots of cool art.

One thing that is very important to understand about the Grateful Dead is that they are the products of a specific time and place. Sommeliers talk of terroir, in which a location’s totality of aspects – geography, climate, soil, terrain, animal life, season, topography, weather – all come together to produce a one-of-a-kind vine that couldn’t be duplicated anyplace else. So it is with the Dead’s timeline and environment. They were all part of the music and broader Bay Area academic and art scenes that grew out of the Beat culture of the ‘50s then into the hippie counterculture of the late ‘60s.

Some background: author Ken Kesey, whose most famous novel is One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, made a home in the forested hills of Palo Alto, north of the Bay Area. He cultivated a group of free-thinkers, artists, and techies who indulged in all manner of left-of-the-dial experiences. Among these was the ingestion of the hallucinogenic drug LSD, then still legal and made available through chemists at UC Berkeley. Kesey’s group, dubbed The Merry Pranksters, began hosting gatherings, first at his homestead and then at other houses, warehouses, and theaters in the area, called Acid Tests. At the Acid Tests, everyone was given the eponymous substance and then exposed to various light shows, performances, sound experiments, and randomness. The events became a huge celebration of weirdness and personal exploration. Before long the Grateful Dead came to be the house band for these happenings, and it was through this experience that they forged their musical ethos and improvisatory approach. The Acid Tests were loose and strange, and the freedom to experiment, stretch out, and take risks (even if they didn’t succeed) were instrumental in the band finding their own identity.

Later, as the San Francisco music scene became more established, people flocked from all over the country to the city’s Haight-Ashbury district. Performers and enterprising promoters began to replicate the Acid Test experience, first in free outdoor concerts, then commercially in dance halls. The Dead, along with compatriots Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe & the Fish, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Big Brother & the Holding Company would play on stage to a crowd of dancers as light shows and videos projected over it all. This was the beginning of the multimedia rock concerts that are de rigueur today. Besides musical performances, these shows also included comedy acts, lectures on spirituality, art exhibitions, etc.. Eventually it all exploded, and they hit the national touring circuit.

For the next 30 years the Dead toured North America and Europe almost constantly and amassed the widespread Deadhead fan base, all while driving several advancements in studio recording and concert presentation. Over such a span of time, there were understandably some lineup changes. Foremost among them is in 1967 when second percussionist Mickey Hart joined up, who apart from a 1971-1974 hiatus has been with them since. Beyond there, the Dead have hosted a revolving door of keyboard players, each signifying a different era for the band. All elements of their sound bubble up to some degree in every era, yet some facets of their sonic personality were emphasized more than others depending on the timeframe and who was playing.

In the mid-Sixties they sounded like your standard garage-rock blues band, but by the end of the decade they had fully immersed themselves into the psychedelic era and led the pack when it came to off-the-wall freak-outs. This first 5-year era is known as “primal Dead,” peaking in 1969. From 1968-1970 Tom Constanten supplemented Pigpen’s bluesy style with more trippy keyboard flourishes, then left amicably. As the hippie scene began to become played out in the early Seventies, the band stepped back from the tie-die fuzz and refocused on the roots of their sound with a more country & folk informed Americana.

During the first 7 years of the band’s existence, Pigpen served as a frontman of equal standing alongside Garcia, but his influence waned due to Weir and Garcia’s budding songwriting, as well as his alcohol-induced health issues. He left the band in 1972, and died of liver failure the following year.

In 1972 the band added Keith Goodcheux to augment an ailing Pigpen. Goodcheux, an extremely accomplished pianist, also brought along his wife Donna Jean to sing vocals. This brought another peak for the outfit. Over the next few years, the Dead opened up their sound with a light touch that drew on very jazzy improvisation. In the mid-Seventies, synthesizer pioneer Ned Lagin (while never an official member) sat in with them often in concert and contributed to a couple studio albums. In the latter half of the Seventies the Dead began to incorporate progressive rock song structures as well as funky, almost disco-like grooves.

The long five years from 1972-1977 is the cross section of the band at its best, highlighting a little bit of it all. While many fans cite 1977 as their best year, the ultimate culmination, for me, is 1974. By ‘74, the Dead had been operating for almost a decade and were playing as a well-oiled machine that had fully synthesized their influences. Yet they were still young and hungry, taking risks and pushing themselves. Any show from ‘74 is straight fire and the perfect example of everything the Dead did well.

The Godcheuxs were dismissed in 1979 due to Keith’s drug use impacting his playing and causing personal frictions. Enter Brent Mydland on organ, who ended up being the longest serving key man. The early Eighties indulged a bit too much in then-current synthesized sounds, but over time they figured out how to integrate them more effectively. For the majority of the Eighties, the Dead were in a sort of doldrums during which they were truly a cult band. Then the unexpected happened in 1987.

The song “Touch of Grey” blew up on the charts, bringing the Dead into the Top 10 for the first time in their career. Their performances now attracted a much larger audience, sometimes condescendingly referred to as “Touchheads.” This period of their career is sometimes referred to as “stadium Dead,” based on the huge venues they played and a more commercial classic rock sound. This marked a rejuvenation for the band, as the increased hype and new songs brought refreshed energy and purpose to their playing. In fact, I’d say that 1989-1990 represents a second group peak.

Mydland died of an overdose in late 1990. From 1991-1992 famed musician Bruce Hornsby sat in on piano and accordion as they workshopped a replacement, who turned out to be Vince Welnick. Welnick held it down on keys for the last few years of the band’s career. In the Nineties, burn out and Garcia’s health problems caused often spotty performances interspersed with worthwhile gems. While the less consistent second half of the Dead’s career (1981-1995) doesn’t hold a candle to what they did from 1965-1980 overall, once you are familiar with the band it’s easy to appreciate what they were doing and pick up on the nuance and spark that would still shine through. Increased age and experience added a sense of poignancy to their ballads, and fun triumph to the rockers. Very worthwhile.

Over the course of their career, the band achieved several accomplishments that added to their legend. In 1969 they used the first 8-track recording equipment in America. They pushed the limits of live sound and amplification, especially in the early Seventies with their Wall of Sound speaker setup. This mammoth rig, among many features, sported an individual speaker for every single string of every guitar. When the Dead went independent and started their own record label in the early Seventies, they consciously fostered a grassroots fan network that built its own industry. They went against all established wisdom and encouraged the taping and trading of their live shows, which ultimately provided free advertisement which became reflected in ticket and merch sales, plus an obsessive and long-lived fan community. Yet the band didn’t have a mainstream charting hit single until more than 20 years into their career. They gave of their time and resources freely to charitable causes, especially environmental ones. In 1978 the Dead performed at the base of the Great Pyramids of Giza during a lunar eclipse, and from 1989 -1995, they were cumulatively the highest grossing touring act in the nation. Did you know that the early internet chatroom development was driven by Deadheads to network, coordinate, and share tapes? Outside of their direct fandom, the Grateful Dead set the template for the entire genre of “jam bands,” which all share the focus on attending and taping live shows, multi-genre cross-pollination, and a quirky, left-of-the-dial sensibility.

Of course, it all came to an end when Jerry Garcia died in 1995. He had been battling drug addiction and diabetes for at least the past decade, and as a result looked far older than his 53 years. Ironically, he had checked himself into a rehab facility a couple days prior to his fatal heart attack, an unhealthy lifestyle catching up to him right when he committed to a positive change. The other guys immediately decided to disband, as the Grateful Dead without their Captain Trips was not possible. They all went on to solo careers and played in various configurations with other musicians over the years, but no one can completely fill Jerry’s shoes. They came close, however, in 2015, when the surviving band members fully reunited as the Grateful Dead to mark their 50th anniversary. With Phish’s Trey Anastasio on guitar and both Hornsby and longtime Deadverse associate Jeff Chimenti on keys, they played 2 shows in San Francisco and 3 in Chicago, and were able to put a satisfying closure on their long strange trip.

I Want to Know, How Does This Song Go?

Now that we have a basic grounding in their personnel and history, let’s face the music. What exactly is it about this band that makes them so special? The Grateful Dead’s music was a seamless fusion of rock, folk, psychedelia, and jazz. They basically took every kind of American music floating around and mixed them up into a stew that was tied to tradition yet completely unique. Like most great bands, much of the magic came from what each member brought to their overall sound. Truly, the Dead would not have been the same with anyone else filling out the lineup.

Bob Weir is a very unique guitarist who plays choppy rhythms high on the neck. Instead of playing the same chord over and over, he would take it through permutations that kept the music varied yet still driving forward. Even though Weir’s contributions are often the easiest to overlook, he provided much of the Dead’s trademark flow. He also possesses a deep, excitable voice that is well suited to up-tempo numbers.

Bassist Phil Lesh is one of the most distinct bassists ever in rock. Because he was only taught to play by Garcia after agreeing to join the band, Lesh played as a lead instrument rather than support. His basslines would often circle around and compliment the melody. Lesh loved experimental music, so he always pushed to take the music into unexpected, abstract areas. Considering that he did all this while still playing off of the drummers to anchor the song is fascinating. His voice is probably the worst in the group, but when he does sing lead his untrained gusto provides a real sense of emotion to the words.

Drummer Bill Krueztman is a wizard: it’s hard to keep time with musicians who are all improvising at once, but somehow he kept the beat while also giving himself room to show off his own considerable chops. Second percussionist Mickey Hart brings his interest in world music for a more varied, complex sound to the beat. Kreutzman and Hart together, collectively dubbed the Rhythm Devils, would often play off each other in marathon drum solos on a wide variety of percussive instruments. Nonetheless, the brief “one drummer” period in the early Seventies is among my favorite periods, largely because Kreutzman was by himself. He was able to play more freely instead of having to keep time with another percussionist.

Then, of course, there’s Jerry. It’s obvious to acknowledge that the lead guitarist is going to have a strong influence on a band’s sound, but it goes doubly so for a musician with such a unique approach. As I mentioned earlier, Garcia first learned to play the banjo, and he carried over the finger picking approach to the guitar. Outside of bluegrass, Garcia also saw jazz saxophonist John Coltrane as a major influence, and applied that sense of exploratory searching to his solos. Garcia didn’t shred so much as produce aural quicksilver: augmented by various pedals and effects, his is a distinct, clear, piercing, emotional sound, like golden dew dripping off of the strings to fall into the dark void of outer space. His voice was thin and reedy yet somehow fit the songs perfectly, like a wry jester hiding a damaged heart. While the Dead avowedly had no true “leader,” it’s obvious that Garcia’s genius was the center around which everything else orbited, both on stage and in the broader realm of the band’s community. By this point in time, even laymen are familiar with Jerry Garcia’s bearded, bespectacled image — he’s a cultural icon, and hands down one of the most influential guitarists of all time.

Now, there are two non-performing band members whom I haven’t yet discussed, and they are just as important as anyone who plays an instrument: lyricists Robert Hunter and John Perry Barlow. Hunter and Barlow were two very different people who at the same time perfectly complemented both each other’s perspectives as well as the mindset of the band and its audience. Robert Hunter had been good friends with Garcia for a long time before the band formed, but didn’t join up with them in an official capacity until 1968. Hunter was the sole lyricist until 1971, when he had a falling out with Bob Weir over the latter changing lyrics during live performances. While Hunter continued to write with the rest of the band, Weir began to collaborate with his longtime friend John Perry Barlow. Barlow would go on to also write with Brent Mydland in the Eighties.

In general, the Grateful Dead catalog is mostly Garcia/Hunter tunes and Weir/Barlow tunes, and covers. There are about a dozen songwriting credits from other band members throughout their career, and almost everyone sang at some point. But the above three categories encompass the majority of the songbook.

Straight up, Robert Hunter is one of the best lyricists in rock history. Like all great poets, he has an ability to convey just the right imagery in a line to capture an exact feeling. His specificity gives his songs a remarkable sense of place. For example, the 1972 song “Loser,” sung from the perspective of a down-and-out cardshark, opens with this line: “If I had a gun for every ace I have drawn, / I could arm a town the size of Abilene.” It’s such an evocative way to set the scene, giving you just the sort of edgy yet world-weary personality you’d want for this character. The specificity of Abilene, a little town in Texas, makes it feel so much more real – you know this guy’s been knocking around for a while.

One of my favorite Dead songs is “Franklin’s Tower,” which is obliquely inspired by the founding of the United States and how we can tap into the aspirations of the original American dream that echoes down through generations. It comes off more like a motivational call to rebirth in a world that has been shaped by, and shapes in turn, our identity:

In Franklin’s tower the four winds sleep

Like four lean hounds the lighthouse keep

Wildflower seed on the sand and wind

May the four winds blow you home again

Roll away the dew

Hunter’s greatest lyrical achievement (in my mind as well as his, apparently) is the song “Terrapin Station.” The track is a suite of 7 parts that cumulatively stand as an ode to the power of story to inspire imagination, which in turn inspires the human spirit and connection to the world around us. It’s basically an ars poetica in song form. It begins with an invocation in the classical sense, the narrator calling on the muses to grace him with their favor: “Let my inspiration flow / in token rhyme suggesting rhythm / that will not forsake me / till my tale is told and done.” He then describes a storyteller performing a romance around a fire. The lyrics then pivot to a more abstract exegesis on what I described as the intangible effects of art and literature. These couple verse are among my favorite, every line packed with weight:

Inspiration move me brightly

Light the song with sense and color

Hold away despair

More than this I will not ask

Faced with mysteries dark and vast

Statements just seem vain at last

Some rise, some fall, some climb

To get to Terrapin

Counting stars by candlelight

All are dim but one is bright:

Rising first and shining best

Terrapin Station

The “Terrapin Station” that Hunter refers to is a metaphorical place where romantic dreams are fulfilled, a place where you can get to anytime you give in to the gestalt of people, nature, and life around you. The use of “terrapin” here comes from the Indigenous idea of the world existing on the back of a giant turtle – the world is stranger and more beautiful than we know, yet we’re still a part of it.

Beyond poetic talent, Hunter was also thematically consistent. Common imagery pulled from westerns, history, religion, and the natural world. Outlaws, gamblers, and the devil featured heavily. His words painted colorful pictures that sometimes made sense, other times seemed to be stream-of-consciousness. Yet it all was in the service of a coherent worldview. Life is one big journey (hence the many travel metaphors), one big adventure for which no one really knows the roadmap. But we can help each other along the path, if we are true to ourselves and open for connection. “Once in a while you get shown the light / in the strangest of places if you look at it right.” His turns of phrase synced exquisitely with the musical zeitgeist of the rest of the band, and the result is magic. There is no overstating the importance of Hunter’s lyrics on the power and mystique of the Grateful Dead, and one of the reasons that generations continue to turn to their records.

That’s not to undercut John Perry Barlow. Barlow had a more street level lyrical voice, which complimented Weir’s earthy, gut-level approach perfectly. He grew up on a Colorado ranch before getting involved in the counterculture, and his lyrics reflect the communal ideology that such an upbringing would instill.

One of Barlow’s most enduring lyrics is “Weather Report Suite,” which speaks to many things, namely the cyclical waxing and waning of the natural world. As winter comes and life seems to die, know that it is part of the plan; that life will come again with spring. This of course can be applied to many ups and downs throughout life. And even in the harshest of winter, we have our loved ones and community to keep us warm. Ultimately, Barlow makes the case that there is a deeper, more intangible worth to the toil that we partake in daily:

The plowman is broad as the back of the land he is sowing

As he dances the circular track of the plow ever knowing

That the work of his day measures more than the planting and growing

Let it grow, let it grow, greatly yield!

What shall we say, shall we call it by a name?

As well to count the angels dancing on a pin

Water bright as the sky from which it came

And the name is on the earth that takes it in

We will not speak but stand inside the rain

And listen to the thunder shout “I am! I am! I am! I am!”

So it goes, we make what we make since the world began

Nothing more, the love of the women, the work of men

Seasons round, creatures great and small

Up and down as we rise and fall

There’s a lot to unpack here, including an allusion to medieval Christian philosopher St. Augustine. But since this isn’t a full-bore literary analysis, I won’t go there.

However I will go to another great song that he wrote with Weir, “Cassidy.” Some background: Beat icon Neal Cassady (most famous for his starring role in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road) was also a prominent member of the Merry Pranksters. In fact, he drove the Pranksters’ tie-dye painted bus Further. His connection to the Beats set him up as a sort of sage to the members of the Dead. Cassady died at age 41 from exposure in 1968, as he walked along the railroad tracks in Mexico, inebriated after a wedding. Two years later, Dead crew member Rex Jackson and his wife Eileen Law had a daughter that they named Cassidy. In the song of the same name, Barlow welcomes the birth of new life with infinite potential, while also eulogizing the passing of another influential life. He sees the similar name as a sign of, not reincarnation, but the continuation of positive energy in the world; a replacement of loss with the bright new generation. The song ends with a heartfelt send off, an acknowledgement that the world continues with or without you, and that’s okay:

Flight of the seabirds

Scattered like lost words

Wield to the storm and fly

Fare thee well now

Let your life proceed by its own design

Nothing to tell now

Let the words be yours, I’m done with mine

Hunter and Barlow naturally complimented each other; Hunter’s high minded ruminations on perception and morality fit with Barlow’s explorations of worldly hardship and acceptance. Beyond that, their words fit perfectly with Garcia and Weir’s chords and melodies. They were just as much members of the band as any instrumentalist, and that gestalt was a major factor in the Grateful Dead’s power and lasting legacy. As fans get lost in the music, the lyrics become homilies that are surprisingly applicable to the ebbs and flows of life.

If You Get Confused, Listen to the Music Play

So that brings us to the one last aspect of the Grateful Dead – the jams. The jamming both makes and breaks the band, as for many people, they get lost by what they see as overly long, noodling passages that don’t go anywhere. These people have yet to see the light.

When we talk about “jamming” in a musical context, we mean collectively improvising music without a preordained start or endpoint. There are many musicians in almost every genre who do this well – particularly in jazz – but the Dead were among the first in the rock world to jam so consistently often and well, to the point that it became what they are most known for. While other rock acts of the time would certainly stretch their songs out live, or add in little changes that made a live reading different from the studio track, for the most part they stuck to the same setlist per tour and played most selections more or less the same way every night. The Grateful Dead were different. They fed entirely off of the collective moment – no set list, and each reading of the song could be remarkably different from night to night depending on what the band, or even a single musician, may bring to the performance. It’s exactly this quality of familiarity mixed with uniqueness that makes the Dead so compulsively listenable. You get the best of both worlds: hearing songs you know and love, yet each instance of a performance being unique to that moment.

Most Dead performances start off normally, with the main riff and verse/chorus/verse/chorus structure. Then once the instrumental break arrives, things get weird. Imagine each instrument as a line, and as the song plays all of the lines move parallel in unison. But suddenly, they separate and all go their own ways, crisscrossing and looping through and around each other. Taken individually it seems like they are moving randomly, with their own logic, but looked at collectively, they intertwine in unique, unpredictable ways to create a picture that you would never have imagined at the beginning. Then, gradually, the lines sync up again as the band seamlessly transitions back into the main song. Such is how it feels to listen to a Dead jam.

The specific strengths of each band member, described earlier, synergize most completely in these freeform passages. Admittedly, sometimes it doesn’t quite gel and they flounder. Other times it’s good but isn’t anything out of this world. Yet when the band hits it, when they are really on fire and cooking, the music that is created elevates beyond what is “only rock & roll” to become a magic sound of the universe. Yeah, I know it sounds hokey, but I’m serious. There is a reason that hundreds of thousands of people across the decades have an almost spiritual attachment to this band. It’s not because of the lyrics, or the scene – the art or the drugs or the community or travel. It’s about the music. When the Dead is on, when their music hits, it is simultaneously beautiful and engaging and challenging and relaxing and intuitive and happy and weird and cool and comforting all at once, and it constantly changes and morphs. The music allows your mind to get lost in the notes and for your spirit to lift off in reverie.Members of the band have postulated that their signature jam vehicle, “Dark Star,” is always playing, and they simply tap into it when the time is right. Once the Grateful Dead have suffused your life, that’s how it always feels. It genuinely feels right at almost any time; their music seems to compliment whatever is going on for you at any given moment. I don’t know how else to explain it. Countless other bands since have based their approach off of the Dead’s style of performance. Many do well, and there’s a couple that are just as good but in a different way. (Particularly Phish. But that’s another blog post). Yet no one does IT just like the Dead. When you hear IT, you know. You’re home.

Keep On Truckin’

So, that brings us back around to here. I have to ask myself: what’s the point? Why would you care that I care so much about this band of old hippies? I ask myself the same thing sometimes. It didn’t start this way. After being exposed to the Dead during that high school cross country trek, I liked a couple songs, but nothing more. Later, in college, I ventured to listen to more of their stuff, just as I ventured into many prominent classic rock bands as I explored music. At the time, it was pleasant but not earth shaking. Given their reputation, I was a little disappointed.

Then, gradually, the music began to grow on me. Like when, after a late night run on a cold night, I sat in my bedroom and listened to “Dark Star” as light from the streetlamp sprinkled through my blinds to make designs on the wall. Or how the slinky grooves of “Shakedown Street” undergirded a game of darts in an old wood-panelled house, bridging our party with that of generations’ past. Or how the ramshackle charge of “Cumberland Blues” mirrors the bump of a country road on a sunny summer day. Over time, the music attached itself to so many memories and feelings in my life; by playing the music, I can connect these feelings with new experiences in the present.

The more I get into the band, the more I appreciate just how rich the Deadhead culture around them is. So many creatives, thinkers, techies, athletes and freaks identify with the spirit of the Dead. There’s plenty of iconography that can pop up to let you know that there’s Heads afoot: the dancing bears, turtles playing instruments, a skeleton dressed as a jester or Uncle Sam, the lightning bolt/skull logo (aka Stealie) or the skeleton wreathed in roses (aka Bertha). I’m often surprised when I meet cool people randomly throughout life who turn out to be part of the tribe. Then again, I shouldn’t be – it makes sense that I’d jive with people who share such an outlook.

As I’ve lived life, I’ve come to learn that few things go down exactly as you expect it. There’s always wrinkles, unexpected challenges, and happy surprises. I am increasingly sure that going forward with positivity, extending a smile and a hand toward others, and providing grace and acceptance toward others is the best way to weather the storms of living. In other words, keep on truckin’. Such as it was for the Dead and their music: every show, every day, is a new adventure. We all improvise: it won’t always be great, but if you leave yourself open to collaboration with others and the possibilities of the universe, it can often be wonderful. The music of the Grateful Dead both reminds me of this and helps to make it feel more possible. As the music flows, so does life, and so do I. “What a long, strange trip it’s been,” indeed.

A Beginner’s Guide to the Grateful Dead

If you are feeling so swayed as to give this band a listen, here is a very basic beginner’s guide. I highlight their 5 “peak” live years, as well as their 5 most representative studio albums. Each selection also lists a key track from the release, and where to go next if you like what you hear. If you find something you like, look for more from around that same time. And don’t listen to what some people say – the studio recordings are good! They are a great way to familiarize yourself with the songs before hearing them explored live. I’ve included the key tracks from each in a Spotify playlist at the end.

(Note, the symbol > means “transition into,” meaning that the band links the songs with a seamless segue of improvised music.)

Anthem of the Sun (1968) – The Dead’s second studio release. It’s their most successful psychedelic studio experiment, as well as their most thorough use of the studio as an instrument. It gets delightfully dense and weird.

Essential Track: “That’s It For the Other One”

Next Step: Two From the Vault [live]

Live/Dead (1969) – The first live album, and still one of the best. Captures the essence of the primal Dead era in front of a hometown crowd. The definition of the West Coast sound.

Essential Sequence: “Dark Star > St. Stephen > The Eleven”

Next Step: Aoxomoxoa [studio]

Workingman’s Dead (1970): The closest the band ever came to an acoustic studio album, this record carries a folky, autumnal vibe. It showcases Jerry, Bob, and Phil’s newly workshopped three part harmonies. Marked the beginning of their Americana era.

Essential Track: “Uncle John’s Band”

Next Step: Dick’s Picks Volume 4 [live]

American Beauty (1970) – The Grateful Dead’s most famous studio album, and track for track, it’s hard to argue. It continues the Americana focus of Workingman’s Dead, except with a fuller, more country oriented sound. Everything about the songs, from their lyrics to melodies to arrangements, is beautiful.

Essential Track: “Ripple”

Next Step: Family Dog at the Great Highway, San Francisco, CA 4/18/70 [live]

Europe ‘72 (1972): Featuring the brief yet potent dual piano/organ lineup, Europe ‘72 documents the Dead’s first tour across the pond. This year marks the culmination of their Americana period, but shows that they can still go far out when the song calls for it. Many people consider this one of the best introductions to the band.

Essential Sequence: “Truckin’ > Epilog > Prelude > Morning Dew”

Next Step: Hundred Year Hall [live]

The Grateful Dead Movie Soundtrack (2005): Recorded across the Dead’s 5-night stand at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom in October 1974, this mammoth 5-CD set is the best single document of the Grateful Dead at the height of their powers. As I’ve said, I consider 1974 to be their career peak; this box contains a perfect cross-section of everything. The band is playing with the Wall of Sound here too, so the mix is extra crisp and defined.

Essential Track: “Playing In the Band” [Disc 1]

Next Step: From the Mars Hotel [studio]

Blues For Allah (1975) – Recorded and released during the band’s year-long touring hiatus, Blues For Allah represents the Dead’s fullest studio exploration of jazz. It’s an instrumental heavy album, with lots of complex, cool ensemble interaction.

Essential Sequence: “Help On the Way/Slipknot! > Franklin’s Tower”

Next Step: One From the Vault (live)

Cornell 5/8/77 (2017) – Long circulated in bootleg form, this fan favorite was finally released in an official capacity in 2017. Many people consider this one of their best shows ever, and it does indeed showcase the features that make 1977 so renowned. The playing is tight and groovy throughout, lending a smooth prettiness to the ballands and a laid-back slickness to the rockers.

Essential Sequence: “Scarlet Begonias > Fire On the Mountain”

Next Step: Terrapin Station [studio]

In the Dark (1987): This album was a surprise commercial smash, and reintroduced the Dead to a new generation of fans. While the production is a bit dated, overall it’s a strong collection of songs.

Essential Track: “Touch of Grey”

Next Step: View From the Vault, Volume Four [live]

Without a Net (1990): Containing selections from performances throughout 1989-1990, this is a great introduction to the Dead’s latter-day peak. The playing is muscular and adventurous, and demonstrates why the Dead remained vital up to the end.

Essential Track: “Eyes of the World” [featuring Branford Marsalis on trumpet]

Next Step: Built to Last [studio]

Happy listening 🙂